Documented gastrointestinal manifestations in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. These gastrointestinal manifestations may predate more commonly described signs and respiratory symptoms, such as cough and fever, by several days (de Souza et al., Song et al., Wang et al.).

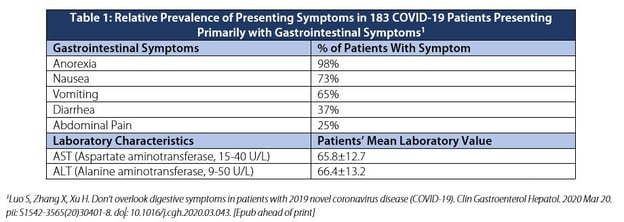

The prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in COVID-19 patients at the time of initial presentation for medical evaluation ranges between 1% to 17% (Chen et al., de Souza et al., Gu et al., Guan et al., Huang et al., Jin et al., Luo et al., Ng & Tilg, Young et al.). Table 1 profiles the relative prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and average transaminase values in 183 patients that initially presented with gastrointestinal symptoms only and were subsequently diagnosed with COVID-19 infection.

Importantly, up to 16% of patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may present primarily with gastrointestinal symptoms and not initially exhibit fever or respiratory manifestations (Luo et al.). Mild-to-moderate elevations in serum transaminases (AST and ALT) were noted upon initial hospitalization (Chen et al., Huang et al., Luo et al., Parohan et al., Wang et al.). SARS-CoV-2 is the presumed pathogen causing these symptoms. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors have been identified as the attachment site for the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and facilitate cell entry. ACE2 receptors have been identified in the upper and stratified epithelial cells of the esophagus as well as the absorptive enterocytes of the ileum (Zhang et al.).

The pathophysiology and transmission routes of COVID-19–induced gastrointestinal disease is under active investigation. COVID-19 patients have been found to shed SARS-CoV-2 in throat swabs and stool samples for up to 2 to 3 weeks (respectively) following initial diagnosis (Gu et al., Ng & Tilg, Tan et al., Young et al.).

To date, characteristic gastrointestinal ultrasound findings in COVID-19-infected patients have not been described. An important application of ultrasound in COVID-positive or rule-out COVID patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms is to identify alternative etiologies for these symptoms (e.g., small bowel obstruction).

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):507-513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. Epub 2020 Jan 30.

de Souza TH, Nadal JA, Nogueira JN, et al. Clinical manifestations of children with covid-19: a systematic review. MedRxiv 2020.04.01.20049833 [Preprint]. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.01.20049833v1 doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.01.20049833

Gu J, Han B, Wang J. COVID-19: gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020 Mar 3. pii: S0016-5085(20)30281-X. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. [Epub ahead of print]

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [Epub ahead of print]

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):497-506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. Epub 2020 Jan 24.

Jin X, Lian J, Hu J, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut. 2020 Mar 24. pii: gutjnl-2020-320926. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320926. [Epub ahead of print]

Luo S, Zhang X, Xu H. Don’t overlook digestive symptoms in patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Mar 20. pii: S1542-3565(20)30401-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.043. [Epub ahead of print]

Ng SC, Tilg H. COVID-19 and the gastrointestinal tract: more than meets the eye. Gut. 2020 Apr 9. pii: gutjnl-2020-321195. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321195. [Epub ahead of print]

Parohan M, Yaghoubi S, Seraj A. Liver injury is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of retrospective studies. MedRxiv 2020.04.09.20056242 [Preprint]. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.09.20056242v1 doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.09.20056242

Song Y, Liu P, Shi XL, et al. SARS-CoV-2 induced diarrhoea as onset symptom in patient with COVID-19. Gut. 2020 Mar 5. pii: gutjnl-2020-320891. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320891. [Epub ahead of print]

Tan LV, Ngoc NM, That BTT, et al. Duration of viral detection in throat and rectum of a patient with COVID-19. MedRxiv 2020.03.07.20032052 [Preprint]. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.07.20032052v1 doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.07.20032052

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 Feb 7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [Epub ahead of print]

Young BE, Ong SWX, Kalimuddin S, et al. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020 Mar 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204. [Epub ahead of print]

Zhang H, Kang Z, Gong H, et al. The digestive system is a potential route of 2019-nCov infection: a bioinformatics analysis based on single-cell transcriptomes. BioRxiv 2020.01.30.927806 [Preprint]. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.30.927806v1.article-info doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.30.927806

*Information from this website is for informational and learning purposes. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, but is intended to share real-time case studies and academic articles within the medical education community.